Cook, along with a group of researchers from the lab of Yu-Chong Tai, Caltech’s Anna L. Rosen Professor of Electrical Engineering and Medical Engineering, has developed a potential treatment that could be a lot less scary and invasive, in the form of a glow-in-the-dark contact lens.

The loss of vision that accompanies diabetes is the result of the damage the disease causes to tiny blood vessels throughout the body, including those in the eye. That damage results in reduced blood flow to the nerve cells in the retina and their eventual death. As the disease progresses, the body attempts to counteract the effects of the damaged blood vessels by growing new ones within the retina. In diabetes patients, however, these vessels tend to be badly developed and bleed into the clear fluid inside the eye, obscuring vision and compounding eyesight problems. As the blood vessels bleed, they cause additional damage to the retina that the body repairs with scar tissue rather than new light-sensing cells. Over time, a diabetic patient’s vision becomes blurry and patchy before fading away completely.

Because damage to the retina begins with an insufficient supply of oxygen, it should be possible to stave off further eyesight loss by reducing the retina’s oxygen demands. Until now, that’s been achieved by using a laser to burn away the cells in the peripheral parts of the retina, so the oxygen those cells would have required can be used by the more important vision cells in the center of the retina. Another treatment requires injecting medication that reduces the growth of new blood vessels directly into the eyeball.

Cook hopes his contact lenses will offer a solution that patients will be more willing to try because the effort involved is minimal, as are the side effects.

Like the laser treatment, the lenses reduce the metabolic demands of the retina, but in a different fashion. Key to their success are the eye’s rod cells, which provide vision in low-light conditions. The rod cells need and use a lot more oxygen in the dark than they do when they’re awash with light—while, say, looking at this computer screen—and it has been hypothesized for two decades that much of the damage caused to the retina by diabetic retinopathy occurs when the rod cells crank up their oxygen demands at night.

“Your rod cells, as it turns out, consume about twice as much oxygen in the dark as they do in the light,” Cook says.

For that reason, the contact lenses are designed to reduce the retina’s night-time oxygen demand by giving the rod cells the faintest amount of light to look at while the wearer sleeps.

“If we turn metabolism in the retina down, we should be able to prevent some of the damage that occurs,” he says.

To provide light to the retina throughout the night, the lenses borrow technology from wristwatches that have glowing markers on their faces. The illumination is provided by tiny vials filled with tritium, a radioactive form of hydrogen gas that emits electrons as it decays. Those electrons are converted into light by a phosphorescent coating. This system ensures a constant light output for the lifetime of the contact lens.

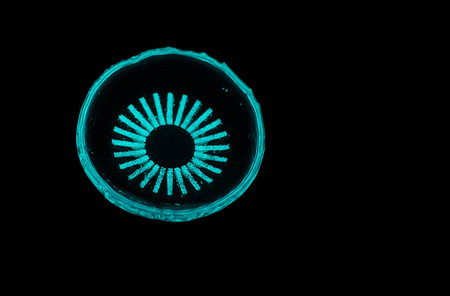

This glowing contact lens could help prevent blindness in millions of people with diabetes. Credit: Caltech

The contact lens as it appears in lighted and dark conditions.

The vials, which are only the width of a few human hairs, are implanted in the lens in a radial pattern like the rays of a cartoon sun. The vials create a circle that is just big enough to fall outside of the wearer’s view when the pupils are constricted in lighted conditions. In the dark, the pupil expands, and the faint glow from the vials can illuminate the retina.

Light therapy for diabetic retinopathy has been attempted before in the form of lighted sleep masks, but results were poor, partly because patients had difficulty tolerating the masks and ignoring the light shining into their eyes as they slept.

The sleep mask light source is not affixed to the eye, so as the eye moves, the wearer sees a flicker and that’s very distracting as you’re trying to fall asleep, he says.

Cook says his lenses avoid that problem by placing the light source on the surface of the eye, so when the eye moves, the light source moves with it, and there is no flicker for the wearer to notice.

“There’s neural adaptation that happens when you have a constant source of illumination on the eye. The brain subtracts that signal from the vision and the wearer will perceive dark again in just a few seconds,” he says.

The contact lens design also ensures that the retina receives an appropriate dose of light throughout the night.

“As we sleep, our eyes roll back. For a sleep mask ,this means the eye is no longer receiving as much light, but the contact lenses move with the eye, so there is no such problem,” he says.

Early testing of the lenses conducted in collaboration with Mark Humayun’s lab at the University of Southern California is showing promising results, with rod cell activity reduced by as much as 90 percent when worn in the dark. Cook says in the next few months, he and his fellow researchers will start testing the lenses to see if their ability to reduce retinal metabolism will translate into the prevention of diabetic retinopathy. Following those tests, they will seek FDA permits to begin clinical trials.

“This is an innovative solution with a potentially huge impact on diabetic retinopathy,” says Tai, who also holds the Andrew and Peggy Cherng Medical Engineering Leadership Chair and is executive officer for medical engineering.

The team recently took their invention to TigerLaunch, an entrepreneurship competition hosted by Princeton University. Their work was recognized as the top medical technology, and the team came in third place overall.

“Having our work recognized by a panel of venture capitalists is really exciting,” Cook says, “but it was the audience members who came up aafterwardand shared stories about loved ones being impacted by the disease who really reinvigorated my efforts.”